Voices and Visions

This issue, devoted to sight and sound

in Whitman, Whitman Studies, and modern

American culture generally presents a range

of work related to the ways in which Whitman

has been seen and heard over the course

of two centuries in the U.S.

Whitman’s house on what was Mickle

Street (now Martin Luther King, Jr., Blvd)

in Camden was a place where sights and

sounds collided for Whitman, as he would

look out his first-floor window and watch

the flow of goods and people going down

to and coming back from the seaport. Later,

not long after Whitman’s death, RCA

built its headquarters just a few blocks

from Whitman’s house, and Camden

thus became the capital of sound recording

and of the manufacture of sound recording

technology. Some years later, in

1933, Camden became the first city in the

country to have a drive-in movie theatre,

synchronizing images and sound.

|

|

The screen tower of the first drive-in at Camden, New Jersey, June 1933.

|

Screen of the first drive-in. Photo from Tim Thompson's Drive-In Theater.com.

Screen of the first drive-in. Photo from Tim Thompson's Drive-In Theater.com.

taken June 1933 |

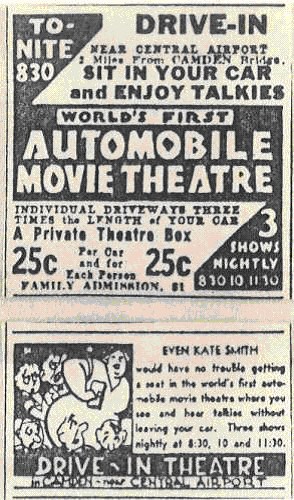

| Ads from Philadelphia's Public Ledger for the opening days of the first drive-in in the world at Camden, New Jersey. Photo from Kerry Segrave's book. Taken June 6th and 7th, 1933 |

|

In this special issue we make available

for the first time a wide range of spoken

word LPs featuring actors reading from Leaves

of Grass and educational videos about

aspects of Whitman’s life and writings. It

is hoped that this archive will be useful

to both scholars and teachers of Whitman

at all levels who are interested in issues

of performance and interpretation.

In keeping with this multimedia and hypermedia

emphasis, the articles, feature pieces,

poetry, and reviews published here address

in various ways Whitman’s performance

modalities and the sites, many of which

splice together sight and sound, in which

performances of his work took and take

place. Ed

Whitley contributes an article

reflecting on his work on the website The

Vault at Pfaff’s: An Archive of Art

and Literature by New York City’s

Nineteenth-Century Bohemians. Elizabeth

Lorang discusses the issues surrounding

the editing of Whitman’s journalistic

poetry for the publicly accessible Walt

Whitman Archive. John Tessitore

takes up the issue of the Boston banning

of the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass and

Whitman’s connection to Free Religion,

putting into a more thorough historical

context how Whitman was seen and heard

by various factions in Boston during those

years.

Zoe

Trodd, who, like Whitley, places Whitman

in the milieu of nineteenth-century bohemianism,

takes care to place him in a longer tradition

of American protest literature, finding

that while “Whitman had sensed earlier

voices,” responding to them in his

work, others after Whitman “listened

back to Whitman’s voice.” She

points out that Whitman is read into and

read aloud at the scene of political protests,

especially those revolving around the gay

rights movement. Jason Stacy analyzes

Whitman’s attempts to negotiate early

consumerism while maintaining the ideals

of artisan republicanism and Hicksite Quakerism

in his exploration of labor and the nascent

consumer economy, locating in his early

journalistic performances a carefully crafted

sounding of public politics.

In feature pieces, the documentary filmmaker

Robert Emmons trains his eye on the Whitman

cartoons of Jeremy Eaton, which, he argues,

have much to tell us about American political

culture through their imagery. Geoffrey

Sill reveals for the first time a

recovered and restored photograph of Whitman

(or is it a photograph of a painting of

Whitman?) derived from one of his famous

sittings; and Michael

Robertson and David Haven Blake provide a useful blueprint,

based on experience, of a communal reading

of “Song of Myself.”

We also offer here, in the Documents section,

Jesse Merandy’s hypertext of “Crossing

Brooklyn Ferry,” a poem that is itself

about the links made between and among

people transhistorically. The poems

of Judith Baumel, Adam Bradford, and Kim

Roberts also help to situate Whitman in

the larger American scene, both during

his life and in death.

Finally, our two crack reviewers—Roberta

Tarbell and William

Pannapacker—weigh

in on Ruth Bohan’s book on Whitman

and visual art and Kenneth M. Price’s

investigation of Whitman and popular culture,

respectively.

Happy listening!

Tyler Hoffman, Editor |