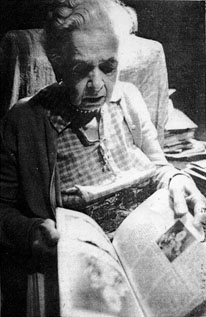

Gertrude

Traubel: Keeper of the Flame

William

Innes Homer, University of Delaware

Gertrude Traubel (1892-1983) played a largely unrecognized role in preserving the memory of her father Horace Traubel (1858-1919) and that of his hero Walt Whitman. Her historical sense and drive for accuracy, however, were commendable. I can testify to this based on numerous interviews I conducted with her at her home at 6362 McCallum Street, Germantown, Pennsylvania, between 1975 and 1979, and at Arden Hall, the nursing facility where she resided in 1980-83. My visits began as a search for information about the artists she had known in New York (so-called Early American Moderns like Alfred Stieglitz and Marsden Hartley). During my visits to her, I developed an appreciation for what she had done to promulgate knowledge about her father and about Walt Whitman and their contemporaries in the world of the arts and social thought.

|

I first witnessed Gertrude’s abilities as an historical annotator in her marginal comments on her copy of The Conservator. She extended this talent to making marginal comments on the literary material that had come down to her from the father and her mother Anne Montgomerie Traubel, who had shared the Germantown home until her death in 1954.To call this house a treasure trove would be a gross understatement. The Traubels seem to have thrown nothing away and thus the building was packed from basement to attic with books, magazines, clippings, letters, manuscripts, ephemera, photographs, and the like, mostly by or related to Whitman, Traubel, and their contemporaries. Some of these items were of routine interest, but many others were valuable historically and financially. Aware of the latter’s rarity, she “hid” them in piles of old newspapers where thieves would not look for them. (During one of my visits, she told me how a robber had come into the house through a basement windowand how she chased him away.) When I entered the picture, most of Horace’s handwritten manuscript for With Walt Whitman in Camden, published and unpublished, was unlocated. But a search through Gertrude’s safe deposit box conducted by her lawyer, Ralph Busser, yielded parts of the diary. The rest, wrapped in brown paper bags, was discovered by me in a second floor chest-of-drawers. Some of the remaining literary and pictorial material was neatly boxed and labeled; but the bulk of the collection remained unorganized—scattered in piles on chairs, on bookshelves, and even on the floors.

When Gertrude’s health began to fail, it became clear that she would no longer be able to manage her home alone. Reluctantly in 1979, she agreed to enter Arden Hall, a nearby nursing facility, and to have the house cleaned out and sold. At this point, I was appointed one of her executors, the other two being Ralph Busser and Joseph Niver, Sr. My job was to go into the house and sort out the contents, retaining what was valuable and discarding anything that could be clearly identified as trash. This task was complicated by the fact that the distinguished Whitman collector, Charles E. Feinberg (d. 1988) had entered into a purchase agreement with Gertrude and her mother in 1953, in which their Whitman and Whitman-related material would go to the Library of Congress as his gift. In addition, Feinberg, Gertrude told me, had offered her a monthly stipend to help her with living expenses during her lifetime. My role as an executor and friend of Gertrude’s was thus to separate material promised to Feinberg from other items that could be given away or sold for Gertrude’s benefit. This was an arduous task.

Eventually, in the spring of 1980, Ron Wilkinson, representing the Library of Congress, came to the Traubel house and removed what they wished to retain for their collections. The residue was donated, by mutual agreement of all concerned parties, to the Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Department. Temple had already expressed interest in a select Whitman-Traubel collection, to be given in part by the Innes family and myself, so this was an appropriate gift. It remained for me to arrange the sale of remaining non-Whitman items in the house: primarily Rose Valley furniture, pastel paintings by Arthur C. Goodwin, and a variety of rare and not-so-rare books. When this task was complete, for Gertrude’s benefit, a clean up firm was employed to empty the rooms.

It is worth noting that a small but interesting collection of original Whitman material was gradually removed from the house by me, eventually going to Charles Feinberg, in accordance with his purchase agreement with Gertrude and her mother. Some of these items were sold by Feinberg at auction through Sotheby’s, New York, December 15, 1986. Included with the Whitman material were letters of particular interest by Alfred Stieglitz, Rockwell Kent, John Sloan, Robert Henri, and others, including Marsden Hartley. The Hartley letters, now in the Library of Congress, served as the basis for the book Heart’s Gate: Letters between Marsden Hartley and Horace Traubel, 1906-1915 (Highlands, NC: The Jargon Press, 1882), edited and introduced by me.

I am grateful to Gertrude Traubel for providing personal reminiscences and documentation that enhanced my work as an historian of art and American culture. She also served as a personal link to memories of my family who enjoyed her friendship and that of her mother and father. But Gertrude played a larger role than this. Her acute historical sense enabled her to preserve a segment of the literary heritage of HoraceTraubel and his idol Walt Whitman and to comment intelligently, by means of thoughtful annotations, on the importance of significant facts and ideas promulgated by these figures. Moreover, she generously shared her knowledge with scholars and students from as far away as Japan and the Soviet Union. It is safe to say that Whitman-Traubel studies would not have been the same without her helpful influence.