The

Rose Valley Press and The Artsman

William

Innes Homer, University of Delaware

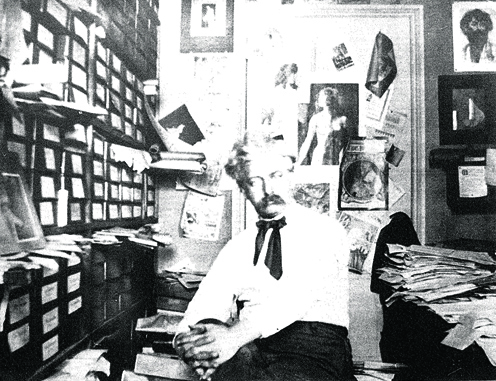

The Rose Valley Press, developed and articulated largely by Horace Traubel (1858-1919), was one of the three official “shops” of the Rose Valley Association. Unlike the others, however, it was based in Philadelphia, with headquarters at 1624 Walnut Street in the building occupied by Price and McLanahan’s architectural firm. (There is no record of a printing shop at Rose Valley.) Traubel established himself n a rent-free office on the third floor at 1624, and there he did his editorial work and handset much of the type for Rose Valley’s journal, The Artsman, and other publications of the Rose Valley Press.

|

|||

Traubel’s interests, however, were not exclusively literary. A humanitarian deeply interested in ethics and social justice, he affiliated himself with the Ethical Society of Philadelphia and under its auspices founded a monthly magazine, The Conservator, in 1890. This journal, which he developed into a progressive social and literary forum, gave him essential experience in editing and publishing. The writer’s grandfather, William T. Innes, for many years publisher of The Conservator (through the Philadelphia firm of Innes & Sons), recalled that Traubel often came to the pressroom and composed editorials by handsetting type at the case. His ability to set type—indeed, to compose in this medium—was the foundation for the Rose Valley Press. |

|||

In

1903, with advice from Innes, Traubel acquired enough type to produce

The Artsman. He seems to have set all of the type himself at

the beginning; later, however, he received help from a Mr. Hibner. Once

the typesetting was finished, the remainder of the work was handled by

others. Plates were made, then the presswork was done by Innes & Sons,

and the printed sheets were bound and mailed by another Philadelphia firm.

The Rose Valley Press thus consisted of both Traubel’s typesetting

at 1624 Walnut Street and his outside contracting for the remaining phases

of the magazine’s production.

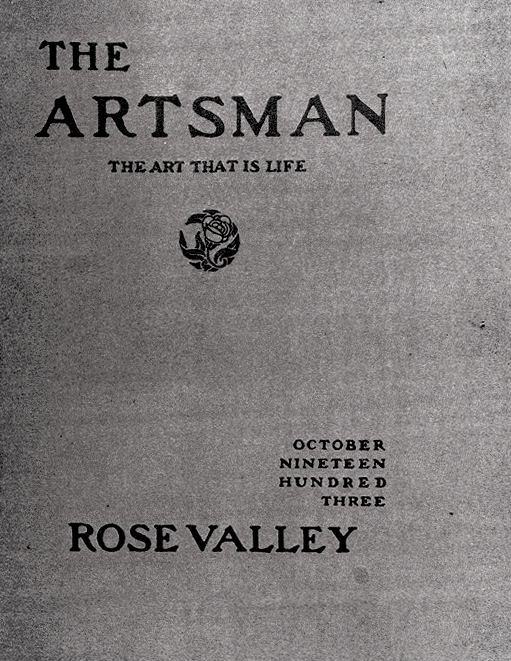

The Artsman

reflected a national and international viewpoint, the chief writer being

Traubel. He often quoted from major figures of the Arts and Crafts movement

and those who inspired them: Ruskin, Morris, Thoreau, Carlyle, and Whitman.

Reviews of other Arts and Crafts activities and publications in the United

States were an important part of The Artsman, and the Rose Valley

philosophies of hand craftsmanship and community life were reiterated

in the column called “From The Artsman Himself,”

which Traubel seems to have written more often than not. The coeditors,

Price and McLanahan, also amply voiced their ideas, with appropriate illustrations,

on architecture and furniture in the magazine’s pages. Some of these

articles were broadly philosophical in concept; others focused upon the

aims of the crafts utopia and construction of furniture made in shops.

Ceramics and wood carving, as well, were discussed by their makers from

the Rose Valley community.

The thirty-three

numbers of The Artsman served as a living record of the ideals,

philosophies, and products of Rose Valley. Although the shops hoped to

become self-supporting, the advertising of their wares in the pages of

The Artsman was low-keyed and unaggressive. In this, the periodical

was much less commercial than the comparable journals issued by Gustav

Stickley (The Craftsman) and Elbert Hubbard (The Philistine).

Traubel’s

layout for The Artsman and related Rose Valley publications followed,

in some respects, the typographical traditions of the English designer

William Morris, but at the same time departed significantly from them.

To Morris he owed the concept of the book as beautiful handmade object,

designed with all the care that might have been lavished upon a painting

or sculpture. His use of wide margins on the pages and occasional contrasting

red and black print recall Morris’ efforts. But Traubel avoided

many of Morris’ mannerisms, eschewing highly decorated, densely

packed pages in favor of a much more open look. Moreover, he broke away

from the more asymmetrical designs reminiscent of Whistler’s. The

American expatriate painter had departed from tradition by arranging type

in off-centered patterns, a method Traubel imitated, though with considerable

restraint.

|

Besides issuing The Artsman, the bulletins, and several announcements of cultural events in Rose Valley, the press offered its services for general printing. In a prospectus, Traubel wrote:

Rose

Valley is determined that its print shall stand for the best results

or that there shall be no Rose Valley print at all. The print must

be like the furniture. It must have a reason for being. Simplicity

strengthens strength. Strength simplifies simplicity. This is true

in all the practical arts. It is cardinally true in the art of the

printer. |

Several

outside organizations and individuals approached Traubel for printing

jobs, but only one of these seems to have materialized: a request by Henry

McBride to produce a brochure for the 1904-05 season of the School of

Industrial Arts at Trenton, New Jersey. The final product, completed after

much negotiation between Traubel and McBride, was executed in the style

and format of The Artsman. The typography, as would be expected,

reflects the highest standards of graphic design.

By comparison

to other American publishers in the Arts and Crafts tradition, Traubel’s

work holds up remarkably well. The Artsman and related publications

of the Rose Valley Press were relatively free of the self-conscious medievalism

and contrived aestheticism found in the printing of Elbert Hubbard’s

Roycrofters. In elegance of design, Traubel’s publications surpassed

the early Morris-inspired issues of Gustav Stickley’s The Craftsman,

a journal comparable in intent to The Artsman, though larger

in scale and format. In quality, Traubel’s typographic work had

its closest parallels wit turn-of the-century products of Copeland and

Day (Boston) and Thomas B. Mosher (Portland, Maine). But Traubel’s

conception remained distinctly his own. Disavowing the influence of William

Morris on the shops, he wrote in The Artsman, “We don’t

want Rose Valley to lean on any one person or to tie to any tradition.

Rose Valley must lead a contemporary life.”

The Artsman

ceased publication with the April 1907 number, marking the end of one

of the finest American Arts and Crafts periodicals. But the Rose Valley

Press lived on in another way: in 1903, Traubel began to issue his monthly

journal The Conservator under the imprint of the Rose Valley

Press. At his offices, first at 1624 Walnut, than 1631 Chestnut Street,

he set much of the type for it by hand and had the presswork done by Innes

& Sons. Consequently, the Rose Valley ideal of fine printing was perpetuated

by Traubel until his death in 1919. The Conservator and the Rose

Valley Press, however, failed to survive him, and thus ended the production

of the longest-lived of the “Rose Valley Shops.”

-Reprinted with permission from the Brandywine Conservancy-

Homer, William Innes. "The Rose Valley Press and The Artsman." A Poor Sort of Heaven A Good Sort of Earth: The Rose Valley Arts and Crafts Experiment. Ed. William Ayres. Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania: Brandywine Conservancy, 1983. 67-71.