Phrenology and Religion in Antebellum America and Whitman’s Leaves of Grass

by Lisle Dalton

Who are you indeed who would talk

or sing to America?

Have you studied out the land, its idioms and men?

Have you learn'd the physiology, phrenology, politics, geography, pride,

freedom,

friendship of the land? Its substratums and objects?

“By Blue Ontario’s Shore”[1]

You are independent, not wishing to be a slave yourself or to enslave others. You have your own opinions and think for yourself. You wish to work on your own hook, and are inclined to take the lead. You are very firm in general and not easily driven from your position. Your sense of justice, of right and wrong is strong and you can see much that is unjust and inhuman in the present condition of society. You are but little inclined to the spiritual or devotional and have but little regard for creeds or ceremonies. You are not any too sanguine and generally realize as much as you hope for.

“Phrenological Description of W. (Age 29 Occupation Printer) Whitman”[2]

Introduction

Walt Whitman’s interest in the “pseudo-science” of phrenology has long been a curiosity and a challenge to scholars. Why would America’s great poet of self and democracy show such a sustained interest in ideas that were, even in his own lifetime, of dubious scientific merit? What influence did phrenology have over his life and art? How should this influence be evaluated? The basic issues have been discussed often by scholars and thus need only to be outlined here.[3] Whitman developed a strong interest in phrenology during the 1840s, wrote positive reviews of phrenological texts, and had his head “read” (a kind of personality analysis and aptitude testing) a number of times. The most important reading, quoted above, was by Lorenzo Fowler, at the time one of the leading phrenologists in the United States. Generally satisfied that the results were an accurate assessment of his character and abilities, Whitman began to use phrenological terminology and concepts in his poems. He also developed a working relationship with the phrenological publishing firm of Fowler and Wells who advertised, sold, and printed some of the earliest editions of Leaves of Grass. This relationship ended abruptly, however, when the firm asked Whitman to edit some of his controversial passages. In spite of this disappointment and the sharp decline in the reputation of phrenology after the Civil War, Whitman remained devoted. He published his 1849 reading five times over his career and continued to use phrenological language in his writing. Towards the end of his life he remarked to a friend, “I am very old fashioned—I probably have not got by the phrenology stage yet.”[4]

Science is the category that scholars traditionally have used to interpret phrenology, hence the common view that phrenology was essentially a set of propositions about the natural world whose validity depended upon demonstration and experimental proof. These ultimately failed, prompting its designation as a “pseudo-science.” A slightly more nuanced historical interpretation holds that the “rise and fall” of phrenology hinged on its status within the scientific community over the course of the nineteenth century. Early interest, mostly on the part of medical doctors, subsided in the wake of critical studies by anatomists and clinicians that emerged around mid-century. Thus while phrenology might have briefly warranted serious scientific consideration, and perhaps even contributed something to the development of neuroscience, it ultimately lost out to more experimentally supportable concepts. Under these kinds of assumptions, Whitman’s sustained enthusiasm for phrenology implies a lack of scientific sophistication, perhaps some intellectual gullibility and stubbornness as well.

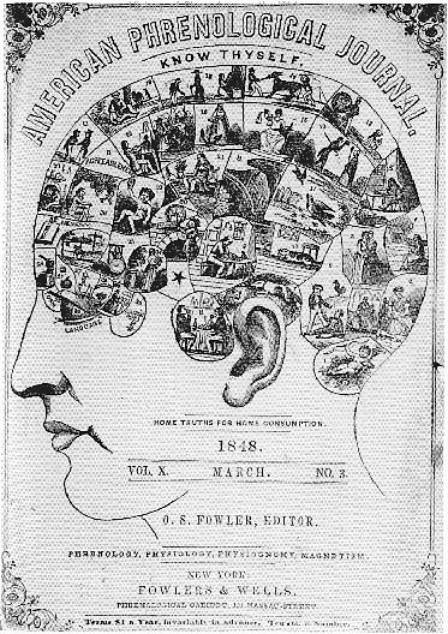

In a broader sense, however, any assessment of phrenology and its influence on artists like Whitman must recognize that it was as much a popular movement as it was a set of claims about the structure and function of the human brain. Its advocates organized societies in cities and towns across the country, penned best selling self-help books, published a highly successful journal, lectured regularly on the lyceum circuit, set up museums, and, of course, measured countless heads. Furthermore, if one is willing to temporarily put aside the scientific judgments of subsequent generations, much can be gained by making a close study of the wider range of meanings and values that antebellum Americans attributed to phrenology. Many, like Whitman, reckoned the novel “science of the mind” as an established natural truth, a reliable method of assessing character, a road map to self-improvement, and a promising resource for social reform. As such, they wove it into the fabric of their lives in innumerable ways. One anonymous contributor to a popular phrenological journal summarized the antebellum “buzz” around phrenology as follows:

This science has drawn aside the veil of metaphysics, revealed in great measure the hidden arcana of the mind, and displayed one of the most beautiful and harmonious arrangements ever yet met with in any known province of the creation…. [T]he path is clear; at each progressive step, new light and beauty burst on the delighted enquirer, and he soon becomes familiar with the few and simple laws which regulate the endless diversity of human character.[5]

Note especially the mixing of religious, aesthetic, and scientific language and the tendency to connect all to an overarching theme of progress. This sentiment was typical of popular phrenology during its antebellum heyday and no doubt would have been familiar to Whitman.

As with any popular movement, a variety of motives—social, political, personal, intellectual, etc.—contributed to the waxing and waning of support for phrenology. This process, as various scholars have detailed, can be only very fitfully correlated to its reputation among scientific experts.[6] Thus in terms of form, content, and meaning, the phrenological movement might be better understood as a variant form of American popular religion. For all its subsequent deficiencies as “science,” phrenology was, at its peak, a richly symbolic attempt to understand human nature and human destiny. As such, it fulfilled the traditional role of religion by directly addressing questions of identity, social relations, and hope for the future.[7]

In what follows, I will examine Whitman’s phrenology in terms of its sources, its cultural context, and, in particular, its religious content. In this reading, his enthusiasm for phrenological ideas and language hews closely to his vision of what religion could be. No systematic theologian, Whitman’s religious views must be gleaned piecemeal from his poems, notebooks, and other writings. A good partial summary can be found in his prose essay, “Democratic Vistas”:

We want for these States, for the general character, a cheerful, religious fervor, endued with the ever-present modifications of the human emotions, friendship, benevolence, with a fair field for scientific inquiry, the right of individual judgment, and always the cooling influences of material Nature.[8]

Whitman’s desire to combine “religious fervor” and “scientific inquiry” into a larger system of meaning was shared by many in his era, and arguably represents a persistent strain of Western thought. Whitman the creative artist, however, had unique expressive talents. Therefore, an examination of his use of phrenology to re-imagine the sacred is of particular value to the study of the interaction between religion and science in American culture.

History of Phrenology

The system of phrenology that Whitman learned in the 1840s was the product of the latter stages of the European Enlightenment, but it had precursors in both Western science and popular culture. Medical theorists at least as early as Galen (2nd century CE) developed theories that associated particular areas of the brain to mental attributes like imagination and memory. Later medieval and early modern thinkers sustained this speculative interest in understanding the precise relationship of the brain to mental activity and behavior. In the 18th century, the Enlightenment’s drive to bring naturalistic thinking to bear on “metaphysical” topics set the stage for the emergence of phrenology. Also during this era, comparative anatomy and German Naturphilosophie (which argued for the unity of structure and function) combined to suggest a basic strategy for studying the relationship of brain to behavior—identify basic mental traits and then go looking for corresponding anatomical structures.[9] A very different line of descent for phrenology can be traced from European popular culture. Divination techniques, such as palmistry and physiognomy, purported to read the inner character and fate of a person from various external markings on the body and thus prefigured the practice of phrenological head readings. As with divination more generally, adepts would be consulted in times of crisis, personal transition, or before momentous decisions. Skilled readers could help the client sustain optimism or strengthen resolve.[10]

Like psychoanalysis, phrenology sprang from the mind of an ambitious Viennese medical theorist, elicited much suspicion and criticism when first introduced, and eventually reached a broad popular audience. Its founder was Franz Joseph Gall, a trained physician who built his “science” on previous theories, observations, hunches, comparative anatomical studies, and correlated measurements of various heads. Gall used the German term Schädellehre, which translates into English as craniology, to designate his ideas, and began lecturing on the relationship of the brain to human behavior to appreciative audiences in Vienna in the 1790s.[11] Around 1800 Gall gained an able assistant, Johann Spurzheim, who helped him codify and promote his ideas.

Suppressed by authorities for allegedly being subversive to religion and morals (a charge they vehemently denied), Gall and Spurzheim decided to take their lectures to other cities in Europe, where they were generally well received. Eventually they settled in Paris, where they produced their foundational four-volume work, Anatomie et Physiologie du systeme nerveux (1810-1819). [12] The book’s main theme was the importance of the structure and organization of the brain and nervous system to any understanding of human behavior. Historians now consider it revolutionary insofar as it advocated a thoroughly biological approach to the study of the mind (vs. theological, philosophical, humoral, or mechanical approaches).[13]

Gall and Spurzheim’s most central

claim was that the human brain was actually a composite of 27 distinct

measurable organs that accounted for all mental activity and behavior. Later

phrenologists would add to this total (the Fowlers claimed 42), but most

followed them in organizing the mental organs into two general classes: 1)

traits shared with animals such as the sexual instinct and self-preservation,

and 2) qualities exclusive to human beings such as the religious sentiment,

wit, and comparative wisdom. Gall and Spurzheim also assumed that the size of

an organ corresponded to its power of manifestation. Thus although all human

beings had the same types of organs, differences in the size and proportion of

specific organs accounted for variations in ability, behavior, etc. Overall

assessments of personality and character looked to a dynamic relationship between

the organs, or sets of organs. General considerations valued the organs in this

second "moral and intellectual" group, particularly in proportion to

the more "animal" organs of the first group, as an index of

intelligence and good character. Finally, Gall and Spurzheim believed that

since the skull ossified over the brain during infancy, external measurement of

the cranium could provide accurate estimates of the size of the organs and thus

the power and relative influence of particular organs on an individual. “Outer” was thus a reliable guide to the

“inner,” and an individual’s “true” self could be “read” from external forms.

This final assumption gave rise to the practice of head reading, arguably the

key to the popular success of phrenology.

Gall and Spurzheim’s emphasis on revealing inner qualities and analyzing innate characteristics should not obscure the fact that they also stressed the importance of environmental influences.[14] Both believed that the various craniological organs responded to external stimuli. Therefore, in theory, positive outside influences could strengthen the desirable regions of the brain—much like muscle tissue responds to exercise. If properly situated, promising brains could be nurtured towards the full development of their potential, while not-so-promising ones could be confined to institutions that would curb their worst tendencies. From Gall onward, most phrenologists considered the various dimensions of religion (worship practices, institutions, etc.) as important environmental influences, thus important to moral and intellectual development.

Spurzheim split with Gall around 1815 and quickly became the key figure in the popularization of what he preferred to call phrenology. A diligent author, lecturer, and social reformer, his efforts were particularly well received in the English-speaking world. Over the next half-century, Britain and the United States would far outstrip continental Europe in terms of their enthusiasm for all things phrenological. In 1832, Spurzheim mounted a lecture tour in the United States that was, by most accounts, a resounding success. His unexpected death in Boston in the fall occasioned an enormous public funeral and publicity that contributed to the spread and acceptance of phrenology. One of Spurzheim’s converts, the Scottish lawyer George Combe, became the third major figure in European phrenology. His most important book, The Constitution of Man in Relation to External Objects (1828) was among the best-selling English-language books of the 19th century. Combe advocated a legalistic version of phrenology that stressed the moral and physiological advantages of adhering to natural law.[15] His tour of the United States (1838-41) has been called the “high water mark” for phrenology among the American upper classes.[16] Intellectuals, professionals and politicians hailed him as a scientific savant and thousands attended his lectures or read serialized versions of them in major magazines.

Phrenology

and Religion

Right

from the start, critics accused the phrenologists of atheism, materialism, and

the denial of free will. They alleged that the phrenological understanding of

mind reduced mental function to the anatomy and physiology of the brain in ways

that denied any significant role for a soul or a transcendent God. Furthermore,

since the organs were supposedly innate, phrenology was accused of fostering

fatalistic expectations about moral behavior and intellectual ability. Often

these critics were Protestant and Catholic authorities who became increasingly

wary of phrenology as it grew as a popular movement. Anti-phrenological sermons

and pamphlets were commonplace in Great Britain and the United States, and

Catholics frequently censured important phrenological works.

Phrenologists

met this challenge in a variety of ways. The most prominent loudly disavowed

materialism while simultaneously touting the utility of a naturalistic

understanding of religiosity and morality. Advocates claimed to have replaced

the “metaphysical” speculation that usually surrounded discussions of religion

and morality with an “empirical science” based upon quantifiable categories and

universal laws. Characteristics such as hope, veneration, conscientiousness,

and benevolence were looked upon as natural qualities of the brain, and,

therefore, as integral to the human constitution as digestion or respiration.

Gall even bragged that he founded a new proof for the existence of God by

isolating a cranial organ dedicated to divine worship.

In

the context of promoting social reform, phrenologists distanced themselves from

charges of determinism by stressing that individuals could improve the quality

of their brains. Head readings provided information about general inclinations

and abilities, and perhaps set certain limitations. With this knowledge in

hand, however, the individual could set about a program of self-improvement.

Training and exercise allegedly brought about an increase in the size of the

desirable organs, and restraint, or “depression,” could curb the influence of the

undesirable. This belief served to deflect accusations of fatalism; innate

endowment was not destiny, just a challenge that was now better understood. It

also contributed to the generally optimistic, albeit often proscriptive, tenor

of phrenological literature. To help individuals reach their full mental and

moral potential, phrenological enthusiasts advocated both institutional

reconfiguration, such as penal and educational reform, and rigorous

self-discipline, which for American advocates included temperance,

anti-tobacconism, vegetarianism, and the reduced consumption of vanity goods.

A physical proof for God, social optimism, and emphasis on individual improvement helped phrenologists find a receptive audience among some religious groups, particularly liberal Protestants in Great Britain and the United States. This success, however, did not fully dispel fears that the phrenological message eroded traditional sources of religious authority. With free thinkers, radicals, and utopians among its devotees, religious critics could make the case that phrenology promoted infidelity. Leading phrenologists worked hard to disarm these accusations, but sometimes added to the confusion by being a bit slippery in regard to traditional revealed religion. All made strategic overtures to Christianity and stressed the compatibility of science and religion. Combe, for example, spoke for many phrenologists when he noted that “God has employed me as an instrument to expound the method by which He governs the world, and how man may accommodate his conduct to the rules of His government.”[17] Orson Fowler, Lorenzo’s brother and one of the leading American apologists for phrenology, expressed a similar sentiment by comparing Christian and phrenological ethics:

Both interdict lust, profanity, drunkenness, gluttony, covetousness, stealing, fraud, malice, revenge, false swearing, lying, murder, and kindred vices; while both inculcate filial piety, moral purity, chastity, honesty, good works, parental and connubial love, friendship, industry, manual labor, self-government, patience, perseverance, hospitality, sincerity, cheerfulness, faith, spiritual mindedness, intellectual culture, and the whole luster of moral virtues.[18]

Yet

at the core of phrenological thought were

many essentially deistic attitudes. The most significant of these were the

emphasis on a creator God who works through natural law and on the natural

religiousness of human beings (innovative for deism in that they located this

“universal” human quality in the natural structure and function of the brain).

Phrenologists also absorbed from deism the tendencies to be anticlerical,

anti-sectarian, anti-creedal, and to be strong advocates for religious

tolerance.

The deism of the major phrenologists corresponded to a teleological understanding of nature that, while rooted in the design arguments of traditional Christian natural theology, also actively embraced emerging views on organic evolution. Like other natural theologians, phrenologists celebrated the intricacies of natural structures, particularly brains and skulls, as objective evidence of divine intelligence and cosmic purpose. Their views departed from the static design, however, in that most championed a form of Lamarckian evolution. Lamarck, a French naturalist, was the first to systematically argue that organic species could change and improve over time. His complex theory emphasized, among other things, spontaneous generation, a concept he called the “sentiment intérieur,” the use/disuse principle, and the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Although rejected by most of the scientific mainstream during the early 19th century, Lamarck’s idea of nature as a law-governed process of progressive development appealed to many liberals and reformers who linked it to their optimistic social theories. Phrenologists were in this camp, and similarly promoted a kind of “use/disuse” principle for mental functions—the notion that the “organs” of the brain could be strengthened and enlarged though “exercise.” Also, many phrenologists, particularly the followers of the Fowlers, believed that if an individual improved his or her phrenological organs the benefits could be passed directly to the next generation through heredity.[19]

Phrenology got its start in America among medical doctors and other educated professionals who formed phrenological societies and study groups in the 1820s. During the Age of Jackson, however, phrenology emerged as a popular movement. The “Introductory Statement” to the Fowler’s American Phrenological Journal, launched in 1838, sketched out the ideals driving this cultural diffusion. In contrast to “monarchical” and class stratified Europe,

knowledge here is every man’s birth-right: and a science whose tendencies are to elevate its votaries to the greatest heights, or to initiate them into the deepest mysteries, is alike the property of all our citizens, who have the inclination and the ability to investigate and acquire it. Science is here the benefactress of every one; she invites all to approach her lights: and the aids prepared to facilitate that approach, must be so presented as to be adapted “to the million;” i.e., it must be, to a considerable extent, elementary; and in one sense of the word, popular. These remarks apply, with reference to the science to whose advancement this journal is devoted. It is a science for the people; they are capable of understanding its principles, of applying them, in more than their great outlines, and of tracing them out, to their results and their dependencies.[20]

Note the subtle use of religious language and idioms—elevate its votaries, initiate into mysteries, approach her lights. Later, the author makes the association between “science” and religion explicit by asserting that the journal would be “evangelical” insofar as it would be “in harmony with divine revelation.” Echoing a common view among antebellum Protestants, it concluded “we conceive evangelical truth to be taught in the bible and a very important species of philosophical truth to be taught by phrenology: and we cannot conceive truths ever to be at variance: we consider these truths to be harmonious.”[21] In context, the phrenologists’ self-designation as evangelical was perhaps a strategy to deflect criticism about alleged infidelities. In a larger sense, however, the “Introductory Statement” aptly demonstrates the antebellum American tendency to blur the lines between popular religion and popular science. Language, goals, and strategies for cultural dissemination were all very similar. Most significantly, antebellum American science and religion shared a way of thinking about the world rooted in democratic idealism, which insisted that vital truth was accessible to all and was to be used for the greatest benefit of all.

Whitman’s early interest in phrenology roughly corresponded to the period of its greatest popularity and influence in the United States, the 1840s and 1850s. Thanks to the aggressive efforts of entrepreneurs like the Fowler brothers, most literate Americans became familiar with the basic phrenological principles and language. Books, journals, public lectures, clubs, storefront museums, busts, and itinerant head readers helped make phrenology a staple of antebellum popular culture. Its language and basic concept permeate the writing of the era, and along with Whitman, most of the major figures of the American Renaissance wrote on the topic (albeit some, notably Melville and Emerson, with considerable skepticism). Likewise, through the work of reformers, phrenology became a familiar feature of schools (Horace Mann was an advocate), prisons, insane asylums, and medical discourse.[22] Whitman of course was a gregarious and catholic observer of American society. His interest in phrenology was part of a larger project of engaging and assimilating the intellectual and popular culture of the antebellum era.[23] Late in life he would summarize his method as “to equip, equip, equip from every quarter … [with] science, observation, travel, reading, study” and then in creative work to “turn everything over to the emotional, the personality.”[24] Alongside the popular “science of the mind,” the vibrant religiosity of the antebellum era significantly influenced Whitman’s work.

Whitman’s Religious Views

A minister, Rev. Mr. Porter, was introduced to me this morning, a Dutch Reformed minister, and editor of the “Christian Intelligencer,” NY. Would you believe it, he had been reading “Leaves of Grass,” and wanted more? He said he hoped I retained the true Reformed faith which I must have inherited from my mother’s Dutch ancestry. I not only assured him of my retaining faith in that sect, but that I had perfect faith in all sects, and was not inclined to reject one single one—but believed each to be about as far advanced as it could be, considering what had preceded it—and moreover that every one was the needed representative of its truth—or of something needed as much as truth.[25]

Walt Whitman, letter to Sally Tyndale, June 20, 1857

Veneration – Devotion; adoration of a Supreme Being; reverence for religion and things sacred; disposition to pray, worship, and observe religious rites. Adapted to the existence of a God, and the pleasures and benefits experienced by man in worshipping him. Perverted, it produces idolatry, superstitious reverence for authority, bigotry, religious intolerance, etc…

Average. – Will adore the Deity, yet often make religion subservient to the larger faculties; with large Adhesiveness, Benevolence, and Conscience, may love religious meetings, to meet friends, and pray for the good of mankind, or because duty requires their attendance; yet are not habitually and innately devotional, except when this faculty is especially excited by circumstances.[26]

Orson and Lorenzo Fowler, Self-Instructor in Phrenology and

Physiognomy

Lorenzo Fowler reckoned Whitman’s main phrenological organ for religion to be average (4 out of 7), and, interestingly enough, available biographical data on the poet confirms much of the predicted behavior for “Veneration, Average”. Of course Whitman’s phrenological reading is but one of the resources for the study of his religious views. In recent years, scholars have looked more closely at his immediate social and religious context, familial and intellectual influences, as well as to close readings of his works for other, more conventional, clues to his religiosity.

As with any antebellum American, Whitman’s immediate religious context was a lively mix of institutions and ideas. Well-established denominations were still the social norm, but also making their mark were upstart sects and experimental utopian groups. In addition, a wide range of religious concepts and practices circulated with limited or no institutional support, such as Mesmerism and Spiritualism.[27] Christianity predominated, but as hinted above, existed in many different, often contentious, forms. New York City, for example, supported Dutch Reformed, Congregational, Episcopalian, Presbyterian, Baptist, Methodist, Unitarian, and Universalist churches (all Protestant), as well as a growing number of Roman Catholic parishes and Jewish synagogues. Growing up, Whitman’s family did not belong to any church, although he did sometimes go to Sunday school. As an adult, particularly during his newspaper days, he fairly regularly visited different churches and would often write about sermons, preachers, church architecture, or sacred music.[28] Whitman’s familiarity with organized religion, however, never convinced him to join a church. Thus he was never “religious” in the conventional meaning of the term, i.e., a member of an organized group who regularly attends worship services.

This is not to say that Whitman was not influenced by the conventional religion of his era. Various religious historians have argued that antebellum Protestantism had the collective power to shape American culture far beyond its immediate sphere of influence in the organized churches. The Protestant worldview set intellectual priorities, defined social habits, modeled organizational structures, and governed the use of language for institutions and persons who were not self-consciously Protestants.[29] For example, Biblicism, rooted in the Protestant principle of “sola scriptura,” deeply marked antebellum American literature. In Whitman’s work this influence manifests in his frequent allusions to Biblical themes, as well as in the similarities of his syntax and rhythm to the widely used King James Bible.[30] Various scholars have also traced the influence of antebellum Protestant preaching in his poetry, particularly that of famed Brooklyn Presbyterian Henry Ward Beecher (also an advocate of phrenology). Whitman’s views on the soul, while idiosyncratic in some ways, were grounded in assumptions about immortality and spiritual agency that were core beliefs for most antebellum Americans.[31] Finally, the reforming impulse and moral intensity found in much of Whitman’s work parallels the direction and tone of contemporaneous Protestant evangelical writing.

Thomas Paine’s famous dictum from The Age of Reason, “My own mind in my own church,” aptly summarizes Whitman’s tendency to think independently about religious topics. Scholars have long noted the deist influence on Whitman and usually credit his father, who familiarized young Walt to the works of Count Volney, Paine, and the feminist utopian Francis Wright. Sam Worley notes that Whitman’s early exposure to deism contributed to his “cosmopolitan and generous willingness to allow for a degree of value in a variety of religious practices.” In his mature thought, this manifested as a “broad and sympathetic embrace of diverse faiths.” Likewise, the benevolent God of deism and its emphasis on an underlying rational design to nature and history contributed to Whitman’s characteristic optimism and holism.[32] What perhaps has not been as fully appreciated was the degree to which phrenology, itself of a strong deistic cant, complemented and extended Whitman’s views. Through phrenology, Whitman’s views on God, tolerance, and the universality of religious impulses were linked to an elaborate theory of mind, a rich descriptive language, and a revealing method of understanding self and identity.

Emerson’s Transcendentalism was, by Whitman’s own acknowledgment, a formative influence. For example, his emphasis on the divinized self owes much to Emerson’s views on the mystical and intuitive as sources of religious authority (vs. traditional religious organizations or scriptures).[33] Emerson’s preference for natural inspiration also had clear parallels in Whitman’s thought. Likewise, the celebration of the miraculous quality of the everyday, a fascination with the spiritual meaning of natural phenomena, and the recognition of the souls in non-human things, all resonated with Transcendentalist themes. Whitman’s emphasis on the body, however, particularly his bold linkage of sexuality and spirituality, distinguished his work from that of his New England brethren. In places, the emphatic body consciousness of the phrenologists seems to have encouraged Whitman’s alternative point of departure for his version of Transcendentalism.[34] For example, in section 24 of “Song of Myself” he proclaims, “Divine am I inside and out, and I make holy whatever I touch or am touch'd from, / The scent of these arm-pits aroma finer than prayer, / This head more than churches, bibles, and all the creeds.”[35]

Another of the seminal influences on Whitman’s religious views was the Quaker reformer Elias Hicks. An itinerant lecturer, Hicks brought a message of the divinity of every person and a sharp anticlericalism to audiences up and down the eastern seaboard during the early national period. Whitman’s parents had been admirers, and Walt himself attended a lecture by the aged Hicks in 1829. Later, he wrote glowingly of Hicks’s influence:

Always E.H. gives the service of pointing to the fountain of all naked theology, all religion, all worship, all the truth to which you are possibly eligible—namely in yourself and your inherent relations. Others talk of Bibles, saints, churches exhortations, vicarious atonements—the canons outside of yourself and apart from man—E.H. to the religion inside of man’s very own nature. This he incessantly labors to kindle, nourish, educate, bring forth and strengthen. He is the most democratic of the religionists—the prophets.[36]

Whitman wrote this tribute near the end of his life and no doubt alludes to his own religious views and sense of vocation in the context of explaining Hicks’s. Later in the essay, he outlines Hicks’s views on the “true Christian religion,” which consists of “secret ecstasy and unremitted aspiration, in purity, in a good practical life, in charity to the poor and toleration to all.”[37] Notably excluded from this list are the mainstays of mainstream Protestantism—“rites, Bibles, sermons, and Sundays.” Thus even before his public and artistic careers had begun (if we trust the aged Whitman’s recollection), Whitman had the intellectual resources and inclination to think “outside of the box” in regard to religion. This was certainly the case with respect to eschatological, or “end time,” theology.

Millennialism

“Millennialism” is a term usually used to designate Christian forms of eschatology. It derives from a reference to a future 1000 year period of Christ’s reign in Revelation 20:4-6. In the text, the reference is part of a larger prophetic vision distinctive for its complex imagery and catastrophic violence. Down through the centuries Christian theologians developed various approaches to eschatological thought, most of which used the millennium as a way of thinking about the historical process. Protestant interpretation, for example, tended toward the Biblical, apocalyptic, and dispensational. The prophetic texts of the Bible, especially Daniel, Isaiah, and Revelation, were thought to hold the key to understanding the trajectory of history, albeit the meaning of these texts required careful interpretation due to their elaborate imagery. What they showed, according to many Protestant interpreters, was that vicissitudes of history had an underlying structure—distinctive stages, or dispensations. Under each dispensation, God set certain rules for religious belief and practice that were to be strictly observed by the chosen. Also, many felt that the final stage, which involved the establishment of an ideal state of existence (the “new heaven and new earth” of Rev. 21) was, at least conceptually, within reach.

Scholars have long recognized the prominence and variety of American Protestant millennialism in the antebellum period, including distinctive forms of premillennialism and postmillennialism, as well as the tendency to associate millennial expectations with a republican political ideology.[38] Premillennialists saw a world in chaos and decline that teetered on the brink of a great cataclysm. Its only hope rested on an imminent supernatural intervention and restoration (the Second Coming) that would privilege those few who were properly repentant and faithful. Postmillennialists, in contrast, believed that Christ would return to earth at some point in the future only after it had been carefully prepared by the earnest and diligent efforts of the faithful. They thus looked to a more distant future “millennium” and emphasized gradual improvements in society through proselytizing and various reform efforts guided by Christian moral principles.

Antebellum postmillennialism often complemented the liberal Protestant program of assimilating the scientific and progressive thought of the Enlightenment into a Christian worldview. Confident that the purposes of a rational God could be understood in terms of a reciprocally binding moral law and discerned in the historical process, modern thought could be embraced and even used as a resource to help secure the future of society and human happiness. In particular, the liberal emphasis on moral law and ethical ideals (love, compassion, equality, fellowship) drew upon the resources of “science” broadly understood as a resource for reform. As James Morehead has noted, American Protestant postmillennial views of progress were tempered by a lingering sense of apocalypse, or the eventuality of some type of supernatural intervention. Thus in spite of their modernism, postmillennialists retained “one foot … firmly planted in the cosmos of John’s Revelation” with is climactic eschatology. Progressive evolutionary views of history therefore were often combined with a sense of history as an epic struggle between good and evil that was central to the Biblical tradition. The Civil War, in particular, brought forth a renewed emphasis on apocalyptic/supernatural themes such as cosmic battles and divine judgment. Others, however, took postmillennialism in decidedly naturalistic directions.

Orson Fowler’s Phrenological

Millennium

The phrenological movement in America embraced persons of various religious persuasions and, in keeping with its deistic leanings, generally took a neutral position on key theological debates. However, the Fowler brothers, particularly Orson, developed a distinctive eschatological perspective during the 1840s and 1850s that combined influences from Protestantism, the Enlightenment, and Jacksonian republicanism. Fowler was a millennialist in the broad sense of the term—one who expected an imminent historical transition into a radically different epoch. Much of this expectation was elaborated in a series of articles entitled “Progression a Law of Nature: Its Application to Human Improvement, Collective and Individual,” published in 1845 and 1846 in the American Phrenological Journal. Certainly analytically cruder than other more celebrated Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment historical theorists such as the Marquis de Condorcet, Auguste Comte, and Karl Marx, Fowler’s work is nonetheless comparable in broad conceptual terms. All believed that 1) historical patterns of improvement were readily perceptible, 2) this improvement would continue into the foreseeable future, and 3) the whole process was developmental—it proceeded in stages organically related to one another and administered by powers and processes resident within history and accessible to human reason.[39] Although clearly, even militantly, secular and anti-supernatural in some ways, these theories resembled dispensational theology. History had an underlying structure and meaning and proceeded in stages governed by distinctive principles. To comprehend the outlines of the total system was to begin to find one’s place and purpose within the historical process.

Fowler’s phrenology held that the mind was composed of 42 separate organs, each corresponding to a particular type of behavior or personality trait. The organs for the “animal and domestic propensities” were located at the back of the head and around the ears, whereas those for the “moral and intellectual” were located at the top and front of the head. In Fowler’s theory of progress, this scheme was projected into the historical process by the association of specific phrenological organs with specific eras. As with the dispensational interpretations, he asserted that history had stages that were governed by distinctive principles. Furthermore, history was proceeding according to a divinely ordered plan that the phrenological system effectively mapped out. Primitive stages, governed by the animal organs, would be succeeded by better eras governed by the higher moral and intellectual faculties. Transitions between stages were brought about through a process of stimulation whereby the faculties that predominated in one period activated those of a higher period. Although all the organs functioned in all periods of history, eventually the more advanced faculties would come into ascendancy and thus would be able to govern thought and behavior. Fowler did not go so far as to postulate a historical period for all 42 of the phrenological organs, but selected certain key organs, or groups of related organs, as the guiding principles in the historical process.

The organs for amativeness (sexual love, libido, passion between the sexes) and philoprogenitiveness (love of offspring, parenting) dominated human life in the earliest stages of history and had been necessary to populate the earth and lay the foundation for later development. Next, the organs of combativeness and destructiveness came to the fore, “explaining” the long history of warfare and societal struggle.[40]

Fowler believed the organ of acquisitiveness (acquiring, saving, amassing surplus, trading, etc.) to be ascendant in his own era and wrote considerably about its sources, distinctive modern bearing, and ultimate necessity in the historical process. As related to historical phenomena, he associated it with the discovery and colonization of the new world, citing Columbus in “his search for gold” and the New England Puritans with their shrewd “Yankee” trading abilities as the progenitors of a new “commercial spirit.” In contrast to the exercise of acquisitiveness in antiquity, the modern period had seen the rise of trade for profit as a general social endeavor. This was a direct consequence, in his way of thinking, of the “phrenological fact” that modern brains were proportionately larger in that area. Although Fowler could rationalize the acquisitive age as necessary to a larger process, his dislike of its excesses was unequivocal. For example, he disparaged the excessive consumption of his contemporaries as “a hundred times more” than necessary for fashion items, tobacco, food, and liquor. In the future, under the influence of moral and intellectual organs, consumption would be reduced to the “standard of man’s actual wants.”[41]

In a later article, Fowler noted that “for the ultimate good of our race,” the reign of acquisitiveness should continue for a few generations. In league with the ascending organ of constructiveness (building, mechanical ingenuity, etc.), property, machinery, and wealth would be amassed for the benefit of future generations. Poverty would be eliminated, labor saving technology made widely available, new areas of land cultivated, and the “earth rendered not only habitable, but a comparative paradise.”[42] Ultimately his views were religious in that a God who worked through natural means and natural laws legitimized this process. By connecting this to phrenology, however, he gave his audience a readily available, and very compelling, reference point for understanding history and looking toward the future. Though the race was young, he confidently predicted, “Progression is its destiny—stamped upon it very constitution.”[43]

Fowler’s views on progress highlighted America’s special millennial destiny and frequently asserted that American institutions would lead the improvement and enrichment of human life. In subsequent issues of his journal he published a number of thematic articles that employed his phrenological theory of progress to analyze advances in the arts, technology, economics, and, in particular, religion. Designed to engage and flatter his American audience, Fowler’s goal was to show how developments in the United States constituted the leading edge of a great historical pattern of improvement.

Fowler’s treatment of religion was basically a Protestant apologetic view of history with a twist at the end—the emergence of phrenology as the key to the next stage of religious development and perfection. In many ways it departed from phrenological writings of the past that had taken two basic positions toward religion. Some phrenologists had downplayed religious topics altogether, largely out of distaste for sectarian polemics, indifference, or the assumption that supernatural religion would fade. Other so-called “Christian phrenologists” understood phrenology as a useful “tool” to be used to support Christian thought and practice. Fowler in other writings exemplified both trends. However, here he moved in a new direction by more aggressively asserting the possibilities of a phrenologically informed religiosity that moved beyond traditional Protestantism. By situating his “science” in the context of religious history, he aimed to demonstrate how phrenology was the next logical step in the development of American religion.

As he surveyed the history of religion from classical antiquity to his own age, Fowler took as his central theme the gradual erosion of detrimental religious authority. Thus Judaism, early Hellenistic Christianity, Roman Catholicism, and, finally, Protestantism all improved upon their predecessors by supplanting unreasonable and unhealthy beliefs and practices. The main target of his critique was what he called “proxy religion”—doctrines and institutions that restrict personal investigation and judgment in religious matters. As discussed earlier, for Fowler the phrenologist, religion was ultimately the result of the exercise of particular organs in the brain, that is to say, a physiological process like digestion or breathing. God had established “by a law written in living characters upon every member of the human family” the necessity of exercising the religious organs. Without personal choice and freedom of thought, religion became distorted, misdirected, depraved, and unhealthy, as would any natural process if unduly restricted or contained. Although Protestantism had done better than its predecessors by proclaiming the “liberty of conscience” necessary to liberate and elevate the religious sentiments, it displayed a distressing tendency to “corset” itself in obsolete “catechisms, general assemblies, and ancient doctrines.”[44] Fowler was encouraged by the “intrinsic vigor” and modernizing trends of the “new schools” in various denominations. Support for these, he claimed, came from the “cream of society” and included many women who were reform-minded and “informed on all the matters of science and morals.”[45] Ultimately he hoped the progressives would lead by example and reconcile with their respective “old schools” so as to “hasten that glorious period of millennial felicity which they shadow forth.”[46]

Fowler’s millennium was as much political as it was religious, and soon after the “Progression” articles, he produced another series on “Republicanism.” These focused on the positive effects of republicanism upon national character and prosperity, or, in his words, upon “the temporal enjoyment of the many.”[47] Implicit throughout was Fowler’s belief that republicanism was the primary source of reform and thus a prerequisite to all progressive economic, religious, and social developments. Fowler’s treatments of the mental and spiritual benefits of republicanism blurred the distinctions between religion, politics, science, and social reform. He regarded the political split from English monarchy during the Revolution as a singular event in the liberation of the American mind, and he celebrated the event in print in glowing, celebratory language: “The sun of universal truth—scientific and religious—dawned upon the human mind when the morning star of republicanism arose upon the darkness induced and perpetuated by monarchy.”[48]

Later sections tended to be longer on gushing paeans to liberty and republicanism than insightful analysis,[49] but Fowler did recognize that the American Revolution had “enfranchised MIND” and in so doing “sundered those feudal fetters which had bound SOUL down to the dogmas of antiquity.”[50] Freedom was also important because it expanded the possibilities for the cultivation of useful sciences like phrenology and the development of self-knowledge—essential to a responsible republican citizenry. For Fowler, the freedom to pursue new knowledge required discipline, and so he set certain limits on behavior. His patriotic prose extolling the grand opportunities of the American experiment never strayed far from his condemnations of even the most minor indulgences. In line with assertions commonly articulated in American Protestant theology, he argued that the price of freedom was moral rigor.

Free minds were the first step towards a “great salvation” that would begin in the United States and gradually spread out across the globe. In this, Fowler’s vision was clearly millennial:

What a mighty revolution is now going on before our eyes, and even in our own souls! The very elements of society are breaking up all around us. We are in a transition state, big with the issues of mental and moral life. What the final results will be time alone can disclose; but one thing is certain—whoever lives to see 1900, will behold a new order of things, and a new race of beings. Most existing landmarks will be swept away and society completely remodeled. A new and greatly improved edition of society, with numerous enlargements and embellishments of humanity, will take the place of those evils and abuses under which we now groan and human virtue and happiness be immeasurably promoted.[51]

Insofar as this was a very physical, temporal vision of the good society (albeit located in the future), religious critics were perhaps justified in their suspicions of Fowler’s dedication to orthodox Christian thought. Although he professed to believe in God, the triumph over evil, and immortality, his millennial views said little about supernaturalism and otherworldly kingdoms. Indeed, in many of his other writings Fowler implied that the careful selection of mates (based upon phrenology and Lamarckianism) was the key to developing a sounder citizenry and, by extension, a better society.[52]

Fowler felt that this better society would not so much replace basic religious ideals of benevolence, veneration, spirituality, and conscientiousness, but, with the aid of phrenology, would do a more effective job of helping people live up to them. “We shall have no new principles of religion, for these principles are as immutable as the throne of God,” he declared, “yet we shall have a new interpretation and practice of them.” Religion thus was to be cleansed of its “perversions, sectarian deformities, aristocratic pride, pomposity, and gaudiness.” On a social level, Fowler envisioned religiosity as being the “habitual practice of goodness” that included, among other things, assisting the poor and promoting education.[53]

Phrenology and Millennialism in Whitman

Hungerford’s early essay on Whitman and his “chart of bumps” notes that in the years immediately preceding the publication of Leaves of Grass, phrenology helped the poet through a “psychic transformation”:

The imaginative hack writer, sentimental and jejune, became the firm and bold prophet of a rich and new life. He became convinced of himself, sure, authentic. He came to regard himself as the natural voice of modern, democratic America, and of healthy men and women everywhere. He became the Answerer, the poet who interpreted life because all life and human nature were implicit in himself.[54]

Building from this insight, Harold Aspiz in Walt Whitman and the Body Beautiful demonstrates how phrenological concepts, those of Fowler’s in particular, shaped Whitman’s views on “personal greatness, the nature of poetry, and the role of the ideal poet.”[55] Among his valuable insights are the connections he makes between Whitman’s sense of self, his vocation as a poet, and his religiosity:

[Phrenology] crystallized his belief that the poet must be a cynosure of manly vigor, whose perfect brain contains those powerful faculties—Ideality, Self-Esteem, and Individuality—which enable him to test the world of experience against his instinctive sense of an ideal world and the correlate material data with spiritual truths.[56]

Aspiz goes on to analyze a number of Whitman’s poems that reflect the influence of phrenology, including “A Song of Joys,” “Unfolded Out of the Folds,” “Song of the Broad-Axe,” “There Was A Child Went Forth,” and “Faces.”[57] Among other things, Aspiz traces the influence of Orson Fowler’s millennial views and Lamarckianism in Whitman’s writings.

Millennialism is also a central theme in David Kuebrich’s Minor Prophecy: Walt Whitman’s New American Religion, perhaps the most thorough study of Whitman and religion to date. Kuebrich’s main argument is that Whitman’s poetry contains a “coherent religious vision” whose elaborate symbolism, nature mysticism, and emphatically experiential spirituality were an attempt to establish a “post-Christian myth” adapted to modern thought.[58] Sustaining Whitman’s project was a historical vision that he developed during the 1840s and 1850s that drew upon republican political writers, social reform literature, and other sources, including phrenological writings. Kuebrich’s summary of Whitman’s views is reminiscent of Fowler’s millennialism:

Whitman’s view of contemporary history and his belief in a millennial future emerge out of his conviction that, as a result of existing political and material achievements, a new religious vision could now bring about the absolute liberation of humanity and disclose vistas of boundless possibility to each man and woman. In order to nurture this new race of humans, Whitman’s vision had to free the American people from their major forms of psychological repression.[59]

Kuebrich notes that while the miseries of the Civil War chastened Whitman’s millennial views, they were never entirely abandoned. His increasing dismay at the materialism and disparities of wealth of the Reconstruction era seems to have been resolved by placing confidence in the progressive nature of history and the eventual emergence of a new stage of history dominated by a race of fully liberated, democratic, convivial, and affectionate Americans.

That his historical vision remained palpably phrenological might be judged by later poems such as “Thou Mother with Thou Equal Brood” (1872):

Brain

of the New World, what a task is thine,

To formulate the Modern—out of the peerless grandeur of the modern,

Out of thyself, comprising science, to recast poems, churches, art,

(Recast, maybe discard them, end them - maybe their work is done, who knows?)

By vision, hand, conception, on the background of the mighty past, the dead,

To limn with absolute faith the mighty living present.[60]

Like Fowler in the 1840s, Whitman sees a world in transition characterized by the remaking of cultural forms by the outward activity of “Brain.” Also, parallel to the liberal reform tradition, “science” becomes an agent of transformation—that which gives authority and vitality to the “Modern.”

In his prose works as well, Whitman uses phrenological language to articulate his views on the synthesis of science, religion, and democracy. For example, in his extended essay, “Democratic Vistas” (1871), he notes:

It is the old, yet ever-modern dream of earth, out of her eldest and her youngest, her fond philosophers and poets. Not that half only, individualism, which isolates. There is another half, which is adhesiveness or love, that fuses, ties and aggregates, making the races comrades, and fraternizing all. Both are to be vitalized by religion, (sole worthiest elevator of man or State,) breathing into the proud, material tissues, the breath of life. For I say at the core of democracy, finally, is the religious element. All the religions, old and new, are there. Nor may the scheme step forth, clothed in resplendent beauty and command, till these, bearing the best, the latest fruit, the spiritual, shall fully appear. [61]

Note that adhesiveness was the phrenological term for "Social feeling; love of society; desire to congregate, associate, visit, seek company, entertain friends, form and reciprocate attachments, and indulge the friendly feelings.”[62] Here Whitman elevates it to a spiritual principle necessary to the healthy functioning of democratic society. Later he writes of a “strong-fibred joyousness and faith, and the sense of health al fresco.” In a passage that resembled the emerging New Thought tradition, he states how a proponent of this new religion “will be known, among the rest, by his cheerful simplicity, his adherence to natural standards, his limitless faith in God, his reverence, and by the absence in him of doubt, ennui, burlesque, persiflage, or any strain'd and temporary fashion.” [63] The buoyant confidence in self and history that had characterized the Fowlers’ writings is equally apparent in Whitman’s.

Conclusion: Whitman’s Legacy to Religion and Science

Whitman

once jotted in a notebook, “Remember that in scientific and similar allusions

that theories of Geology, History, Language, &c., &c., are continually

changing. Be careful to put in only what must be appropriate centuries hence.”[64] The obscurity of some of his favorite

phrenological terms today, however, suggests that Whitman might have erred in

borrowing so much from the “science of the mind.”[65] References to amativeness and adhesiveness

in his works often puzzle contemporary readers, and terms such as philoprogenitive have all but

disappeared. Even during Whitman’s lifetime, the reputation and relevance of

phrenology seriously declined. Although the Fowler family kept up their

activities into the 20th century, arguably much of the

entrepreneurial creativity and intellectual energy that went into American

phrenology in the 1840s and 1850s gave way to routinization, retrospection, and

defensiveness.[66] Tellingly,

the American Phrenological Journal

during the late 19th century often reprinted defenses and

endorsements of their views that had been written decades earlier.

Judging

from the dismissive treatments in influential medical textbooks, mainstream

American science seems to have decisively given up on phrenology much earlier,

around the time of the Civil War.[67]

In some disciplines there was a lingering influence, as seen in the

localization of mental function in neurology or collections of skulls in

physical anthropology. Also, the Lamarckian themes championed by the

phrenologists and Whitman would be taken seriously throughout the 19th

century, particularly in the United States.[68]

However, during the Gilded Age, a number of new scientific developments arose

that stepped into the role that phrenology had enjoyed in both the artistic and

the popular imaginations. Darwinism, the social sciences, and psychological

theories of the unconscious, for example, increasingly became more influential

in terms of explaining the human condition and charting its future

direction.

On the religious side, it should be noted that Whitman himself often referred to his work as an effort to “drop in the earth the germs of a greater religion.”[69] During his lifetime and after, admirers formed study groups and clubs devoted to his poetry and ideas. A few of these had cultic dimensions (ritual readings, anniversary celebrations, etc.) that might be compared to religion.[70] And, of course, his work is now fully canonical in the nation’s literature, and as widely and reverently read as that of any American poet.[71]

Nevertheless,

the religious institutions and sectarian tendencies that Whitman (and many

phrenologists) hoped to transcend proved to be extremely resilient. Likewise,

Christian eschatological thought continued to exert a powerful influence over

the American historical imagination. Although there were significant shifts and

mergers after the antebellum period, organized denominations and churches

continued to dominate the American religious landscape. Liberal or “mainline”

forms of Protestantism by and large have accepted scientific innovations and a

progressive worldview. These groups, however, saw no reason to abandon

Christian ideals and symbols, even though they were frequently reinterpreted.

Their eschatology wavered between postmillennialism and amillennialism (the

view that no specific time frame can be established for the end of history and

that apocalyptic texts should be interpreted allegorically). The former was

most influential in the late 19th century, a period of rising

optimism associated with scientific, technological, and economic developments.

The latter became more common in response to the challenges to the idea of

progress posed by the traumas of the 20th.

Beginning

in the late 1800s, Conservative Protestants mounted a sustained, sometimes

militant, dissent against liberal and modernist theologies that they believed

undermined core doctrines, moral standards, and Biblical authority. Over time,

the Conservatives grew and diversified such that today the term encompasses

Fundamentalist, Pentecostal, and Evangelical groups. Among other things,

Conservative theologians reasserted the centrality of a Biblically informed

premillennialism, and often interpreted the great wars and persistent social

problems of the 20th century as “signs” that the supernatural

intervention and final cosmic battles predicted in Biblical apocalyptic texts

were right around the corner. This premillennial eschatology pointedly rejected

notions of a progressive evolutionary worldview. Its influence over the

American popular imagination might be measured by the impressive sales of

apocalyptically themed books, as well as polls indicating that approximately

45% of Americans utterly rejected the idea of evolution.[72]

Given

the obsolescence of his preferred “science” and the staying power of forms of

religion that he had hoped to transform, how are we to assess Whitman as poet-

prophet of a “new religion” of self and progress? Was he merely a cobbler of

ephemeral ideas whose efforts quickly became obsolete? Did he fail to deeply

influence the way that most Americans regard the relationship between religion

and science? Certainly some of the evidence from subsequent American religious

history points in that direction.

However,

if we look more to Whitman’s underlying way

of thinking rather than the specific references he made, his phrenologizing

perhaps has a more enduring legacy. A late essay from Emerson can help. After

having disapproved of phrenology for most of his career,[73]

he eventually came to appreciate the movement as a crude but significant

expression of the mental disposition of American popular culture. In an 1880

lyceum lecture that assessed the enormous impact of “modern science” on the

“religious revolution” of the antebellum era, Emerson noted:

There was…a certain sharpness of criticism, an eagerness for reform, which showed itself in every quarter. It appeared in the popularity of Lavater’s Physiognomy, now almost forgotten. Gall and Spurzheim’s Phrenology laid a rough hand on the mysteries of animal and spiritual nature, dragging down every sacred secret to a street show. The attempt was coarse and odious to scientific men, but had a certain truth to it; it felt connection where professors denied it, and was leading to a truth which had not yet been announced.[74]

Emerson’s comments prefigure the appreciation for the transitional role of phrenology often found in later evaluations of the movement by social scientists.[75] All regarded phrenology as significant because it had militated against the control of ideas by a religious orthodoxy and agitated for intellectual and institutional innovation. In doing so, it prepared American culture for more substantial changes that would come later. But Emerson’s appreciation of phrenology also implied an attitude rather different from those, such as historian John Davies, who concluded that phrenology was “a way station on the road to a secular view of life.”[76] While not disavowing science per se, Emerson’s references to “a felt connection where the professors denied it” suggested that palpably religious criteria—the emotive, the synthetic, and the holistic—were to be considered alongside learned opinion. Hence, phrenology, in spite of the disdain of experts, could be appreciated in historical perspective as an attempt by average Americans to develop a meaningful understanding of themselves and their world.

For his part, Whitman’s best efforts at a “felt connection” were his poems that link the personal and the cosmological. In “Kosmos” for example, he writes:

WHO includes diversity, and is Nature,

Who is the amplitude of the earth, and the coarseness and sexuality of the earth, and the great charity of the earth, and the equilibrium also,

Who has not look’d forth from the windows, the eyes, for nothing, or whose brain held audience with messengers for nothing;

Who contains believers and disbelievers—Who is the most majestic lover;

Who holds duly his or her triune proportion of realism, spiritualism, and of the aesthetic, or intellectual,

Who, having consider’d the Body, finds all its organs and parts good;

Who, out of the theory of the earth, and of his or her body, understands by subtle analogies all other theories

The theory of a city, a poem, and of the large politics of these States;

Who believes not only in our globe with its sun and moon, but in other globes with their suns and moons,

Who, constructing the house of himself or herself, not for a day but for all time, sees races, eras, dates, generations,

The past, the future, dwelling there, like space, inseparable together.[77]

Hints to phrenology might be inferred from references to the brain, good organs, and theories of the body. But in a larger sense, the poem evokes an epistemology that Whitman and the phrenologists shared: correspondence, or the belief that microcosm “corresponds” to—i.e., replicates and sympathizes with—the macrocosm. Religious beliefs and practice based upon correspondence are among the oldest and most widespread in the world. They can be found, for example, in astrology, which assumes that individual fate is related to celestial bodies, in traditional Native American orientation rituals that seek to harmonize worshipers with their immediate natural environment, and in divination practices that “read” external signs on the body for clues to character and destiny.[78] The phrenologists, whose favorite text was entitled The Constitution of Man Considered in Relation to External Objects, can be understood as modernizers of correspondence theory. Although much influenced by the scientism of the Enlightenment and the emergence of evolutionary thought, they nevertheless have one foot in this very ancient way of understanding and relating to the world.

In Whitman’s poetic rendering of correspondence, an inquisitive and active microcosm seeks out macrocosm in ever more expansive ways. In the first section diverse knowledge of self is gained through nature, experience, various philosophies, and the body. In the second section, the self and its “theory” find connection through “subtle analogies” to externalities—locale, art, politics, cosmology, and human history. And in the end, the process is profoundly religious. The final line evokes the classic aims of mysticism—the unification of self with all that is, and the transcendence of space and time.

In

present day American culture perhaps the most conspicuous heirs to Whitman’s

way of thinking are various “New Age” groups that share much of his vision for

a synthesis of religion and science (albeit with updated scientific concepts).[79]

New Age thinkers also resemble Whitman in that they tend to distrust

traditional religious institutions, draw from diverse sources of inspiration,

promote modernized versions of correspondence, and expect an era of peace,

unity, and prosperity to emerge in the near future.[80]

But for the more conventionally religious, even the irreligious, steeped in a

culture profoundly shaped by scientific ideas and institutions, his

“phrenological” poems perhaps carry a more basic message. The quest for new

knowledge is rooted in the deeper psychic needs and impulses of the self. These

are diverse, contradictory, and sensuous, but given the proper cultivation,

they can lead to mystical insight. Thus even in an age of scientism, the self

has the potential for divinity. Whitman’s project of bringing a distinctive

religious sensibility to the “scientific,” a creative fusion of ancient

intuitions and modern enthusiasms, remains a significant dimension of his

legacy. It was, it part, the fruit of his long engagement with phrenology.